In recent times, we might be forgiven for thinking we were living in a Russian play. When Irina, the youngest of Chekhov’s Three Sisters, says, “How are we supposed to go on like this?” most of us would probably just shrug fatalistically and look glumly at the other two sisters.

Besides being a playwright, Chekhov was master of the modern short story, and often wrote offering guidance to fellow writers: “Don’t tell me the moon is shining,” he would admonish them. “Show me the glint of light on broken glass.” Isn’t that incitement to vandalism or burglary?

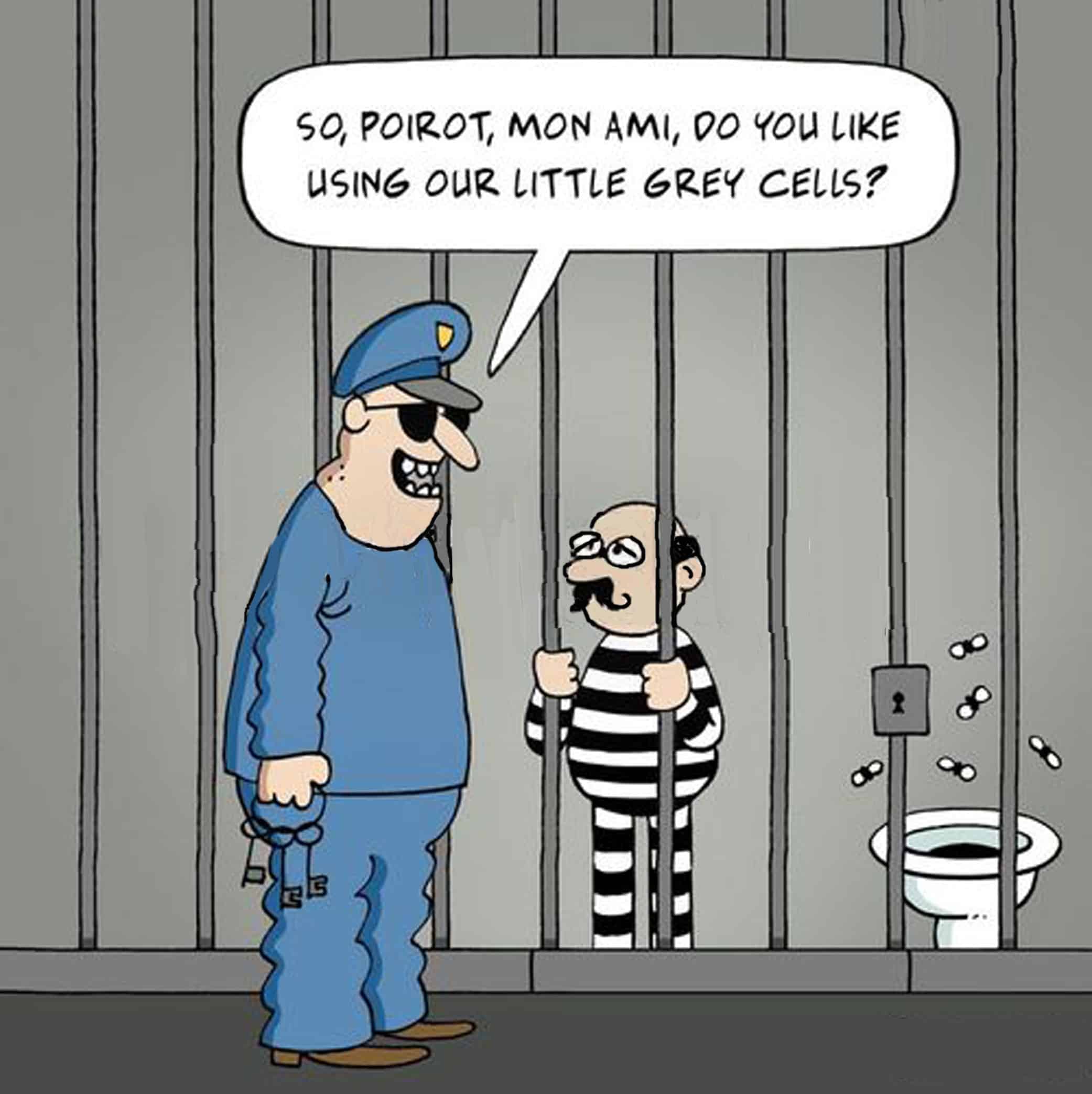

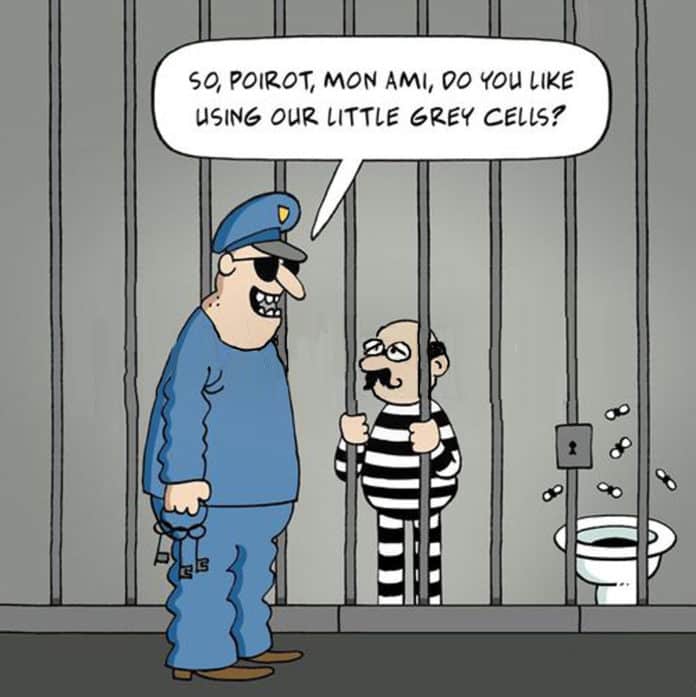

His most famous piece of advice is called ‘Chekhov’s Gun’: “If in the first act you hang a pistol on the wall, in the following act it should be fired. Otherwise don’t put it there.” Now he’s graduated to wounding and manslaughter. Clearly Chekhov wasn’t a fan of red herrings, so it’s probably just as well he didn’t live long enough to read Agatha Christie, although their lives did overlap. To Chekhov, little grey cells were where dissidents ended up.

Incidentally, isn’t it strange that there are around 200 species of herring, and not one of them is red?

We are all living with drama now, after a fashion, although in most cases not a fashion we hope will catch on. Modern dramatists would have us believe that talking solves everything, especially when we gather in the study (or train carriage) to listen to Hercule Poirot’s brilliant explanation of how the culprit murdered the deceased. There’s usually a woman or a will involved, sometimes both.

But much of the time talk is cheap, especially compared to a picture that is worth a thousand euros. Yet when we are feeling low, various people offer us ways to get high on words. Talk to a counsellor, an adviser, one of our sales people, a no-win-no-fee lawyer, a psychiatrist, a top TV chef, a bakery expert, a fitness instructor in a leotard, or ask your satnav for advice if your life is going in the wrong direction. “Words, words, words,” said Hamlet, and you may end up as loony as he was if you don’t watch out, it can easily happen, look at me.

Poor old Chekhov suffered terribly from tuberculosis, but that didn’t prevent him from helping out as a doctor in the cholera pandemic of 1892, when he spoke out against injustice in the distribution of resources between rich and poor countries. “Plus ça change,” he might have remarked, looking at our pandemic, although he would have said it in Russian, perhaps. (Or with a Russian accent.)

Chekhov visited Sakhalin, just as Biggles did in Biggles Buries a Hatchet, when he went there to rescue his arch-enemy Erich von Stalhein, who was imprisoned on that island. Biggles’ creator, Captain W.E. Johns, doesn’t make it clear exactly where the hatchet is going to be buried. Had he previously mentioned a hatchet in a glass case on the wall, possibly, like Chekhov’s Gun?

David Aitken