Exploring your genealogical past is a fantastic way to learn about your ancestors, your family, and yourself. Most public school students have put together family trees that represent the nucleus of maybe two or three generations of people.

Beginning an ancestry journey is an exciting opportunity to learn about history with an intimate and personal approach. However, it is super easy to mistakenly put strangers you’re not related to a branch of your family tree.

Take the time to plan your research. Know what you’re looking for and where those documents can be located. Accept genealogical research is more of a treasure hunt than instantaneous revelations about where your people are from.

1. Assess the Resources Readily Available to You

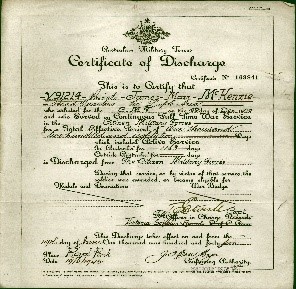

Dated objects are going to help the most as you delve into your family’s past. Postcards, photos, military records, birth certificates, letters, and anything else that may hold clues are excellent jumping-off points for genealogical problem-solving. Get everything organized by date and by the family branch. Make an inventory of what you do have. Reviewing your resource inventory will help you figure out what facts you need.

2. Set Up a Research Method

After you’ve completed your resource inventory it is time to decide how you’re going to structure your research process. It is wise to know the basics relating to the Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS) set by the Board of Certification of Genealogists if you’re concerned about verifying your work!

Regardless of the objectives, your research will require binders, folders, flash-drive (used only for ancestry work), and a logbook. The logbook should be consulted before every session, doing so will save you from repetitive searches and provide guidance for further steps. Also, future family sleuths won’t have to start from scratch if they have your logbook!

3. Talk to Living Family Members

The best resource available to any ancestry buff is their family. Immediate or extended family members are the easiest way to access artifacts and memories. Once these individuals have died, all of their knowledge disappears. Take advantage of social media to reach out to cousins and parts of your family you haven’t seen for ages.

Schedule the interviews like an appointment. Arrive prepared with your logbook, interview questions, pen and paper, a digital recorder, and any memorabilia you might need to be verified. Structure your interview questions to suit your subject and allow them to wonder as they remember the answers.

If you notice your interviewee is reluctant to discuss any specific topics, don’t push them. These memories might be painful and leave them feeling vulnerable. There are plenty of other resources available that provide answers without harming others.

4.Vital Records

Records and photos are the bread and butter of genealogical proof.

A birth, marriage, or death certificate can confirm essential details necessary to confidently complete your family tree.

Be mindful that names change depending on their life events.

5. Faith and Occupational Service Records

Eventually, you will come to an obstacle to understanding your family history. Getting creative pays off. Look for case studies with similar issues as your research and identify new potential leads. Finding out where someone was born, married, or died can often lead to other details that assist in the search.

Keep your eyes peeled for clues like if a midwife-assisted with a birth, directions to an old, family cemetery, and causes of death. These details create a bigger picture of your ancestor’s life and help pull together a more comprehensive look into the time.

Faith, military, and occupational records are another very useful place to find information. Dig into attendance rolls, baptismal records, awarded medals, and census records

6.Perform ‘Reasonably’ Exhaustive Research

The Certification of Genealogists list ‘reasonably’ exhaustive research as the first Genealogical Proof. Ask if there are multiple sources of evidence from different origins? What is the quality of these resources? For example, if a death certificate is substantiated by a family member, an authentic burial record, and the grave is indeed in the right location, then the accuracy of the claim is well-supported.

7. Cite Your Sources

A tenant of proper research in any field is the replicability of the research. By citing your sources and keeping a disciplined, genealogical logbook you’re making it possible for others to replicate your research, allowing them to support or criticize your claims.

Include the title of the document, source or author, publication date, and the location of the document with a copy of it for your binders. Websites like Family Search and Ancestry have databases where you can store your information, but keep in mind that these non-profits and business organizations aren’t obligated to keep your data in perpetuity. It’s prudent to have a dedicated flash-drive to fully backup your ancestry investigation.

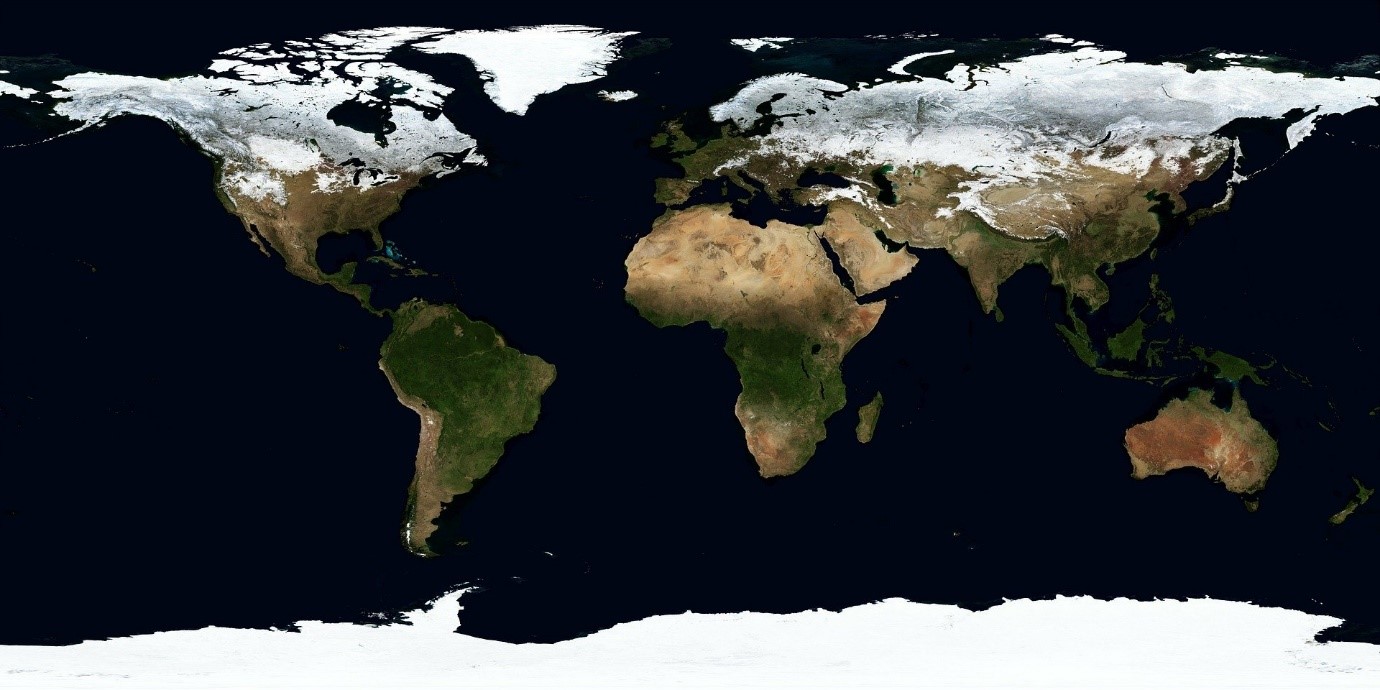

8. Migration & DNA

Knowing where your ancestors were born, where they lived, and where they died can tell you a lot about your family’s history. A map of movements and geographical information can provide a treasure trove of clues in the form of items like passenger lists and migration documents. These resources may get you closer to understanding that individual’s life story.

DNA tests allow you to explore your deep ancestry, assess health threats, and support migration movements of more recent ancestors. Not all DNA tests or services are valuable. Many services are divided by the type of DNA examined (Y chromosome, mitochondrial DNA, and single nucleotide polymorphism). DNA Weekly offers a free service that compares DNA tests and provides educational support in understanding DNA results.

9. Acknowledge Discrepancies

Part of being a proficient genealogist is admitting when there isn’t enough information to factually prove a claim and the willingness to acknowledge discrepancies. When reviewing your research ask if the claim supports other facts in the family tree? How dependable are your sources? Are there missing pieces of the puzzle still?

10. Dedication, and Flexibility

Completing a family tree will eventually test your dedication to your genealogical investigation. Roadblocks are bound to pop up the further back you go. Ancestry research requires a flexible attitude because names, dates, and locations can be just potential facts versus actual ones. The ability to try a solution that fails without giving up is necessary for every family sleuth.