- MUSEO HISTORICO MILITAR DE CARTAGENA

The Military Museum of Cartagena was opened as a Museum on 11 June, 1997 in what, for over 200 years, had been the major artillery base and the headquarters of various artillery regiments in South-East Spain. It was one of a series of major depots dedicated to the storage of equipment, ammunition, repair and manpower and as such it played a major part in many of the conflicts from 1786 to 1976.

It was originally built as ‘El Real Parque y Maestranza de Artilleria’ during the reign of Carlos III started in 1767 and finally finished on 25 August, 1786. The building was designed and the construction overseen by Ferignán-Vodopitch, one of the leading military engineers of his time who was also responsible for finishing the ‘Arsenal’ which was being developed as a major Naval base. From 1716, when it serviced galleys until 1782, when (along with El Ferrol, Cadiz and later Majorca) it became one of the four major bases for the Spanish Royal Navy, with many of the original buildings still standing today.

Between 1765 and 1789 in tandem with the artillery and naval development of Cartagena, the massive walls, which at one time encircled the whole town including the naval and military bases, were being built. They are still known as ‘La Muralla de Carlos III’, (The Walls of Carlos III) and around 70% of the 5 kilometres of wall are still intact.

Despite severe damage during the Cantonal War and the Spanish Civil War, the artillery and naval buildings that date from this period have remained in use and are now used for education or Museum purposes. The Arsenal remains the major Mediterranean naval base of the Spanish Navy.

The Military Museum at Cartagena is one of a number of similar establishments around the country, including the islands, all of which are military bases. Cartagena has three serving army officers as its core staff, with a team of civilian guardians/security staff and another team for the maintenance of the building. However, all the conservation, repair and research work and much of the curating of the collection is carried out by Spanish and British volunteers through a registered cultural association “Amigos del Museo Historico Militar de Cartagena”.

It is the volunteers who do everything from restoring and repairing tanks and heavy artillery, to painting the exhibits, to curating the small-arms collection and the Guinness Book of Records registered collection of military miniatures. They also provide organised tour guides in several languages and there are also a Spanish and a British researcher working on various aspects of the City’s history.

The Museum is in several parts. The upper galleries show the development of Cartagena and the history of the artillery park, with some stunning scale models of the city and explanations of the City’s history on wall boards, in Spanish and English.

There are also video displays showing particular points in Cartagena’s history, for example, the Cantonal Wars of 1873/1874 when Cartagena and eighteen other regions in Spain declared independence from the central government. Cartagena went much further than any of the other Cantons going as far as appointing Ministers and issuing their own currency.

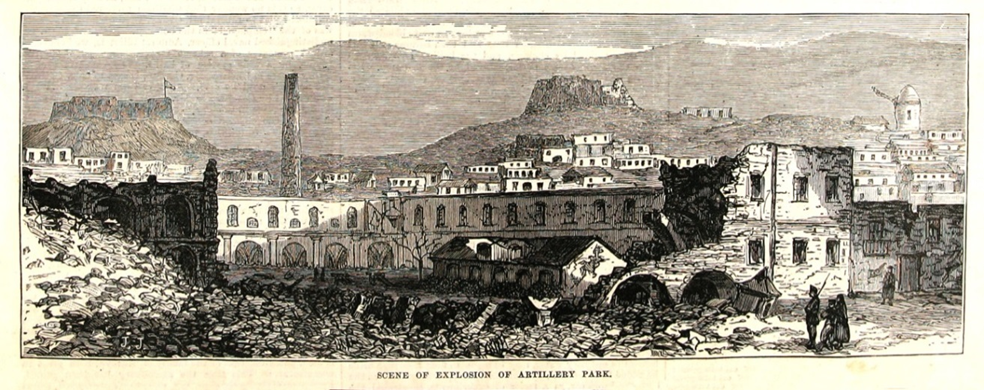

When Cartagena finally surrendered, only 17 buildings in the city were left intact, the town having received 26,976 shells from the 12 Government batteries surrounding the City, the whole exacerbated by a lucky shot from a government artillery position which hit the artillery magazine. An already ravaged City saw a massive explosion, killing 400 and injuring over a thousand inhabitants.

This was the first time that war photography was used in Spain, something that we take for granted today, so images from the siege were transmitted around the world to give a much more immediate feel for what had happened. Fortunately, the Museum is housed in the part of the Artillery Park not razed by that explosion.

Another room is dedicated to the Civil War. It explains the circumstances around the sinking of the ‘Castillo de Olite’, a Nationalist troop and transport carrier, on 7 March, 1939 shortly before the end of the Civil War. 1,499 Nationalist soldiers were killed in what was, by any measure, a complete logistical and communications mess, the largest loss of life in a naval engagement in the Civil War – the naval engagements and the role of the navy are rarely discussed in Civil War histories and almost glossed over in Cartagena’s naval museum.

The ship was sunk close to the entrance to Cartagena harbour by a 152, 4/50 Vickers gun, similar to the gun on display in the Museum, another of the British weapons bought in 1926 and installed from 1931 to 1933 as part of the strategic Defence Plan of that year.

The upper galleries also house the collections of flags (banderas), uniforms, small arms and the world-record holding collection of military miniatures which currently stands at over 3,000 items with more in the pipeline, it is an Airfix kit builders dream!

There is also an Enigma Machine, supplied to the Spanish Nationalist side during the Civil War, as was a good deal of the large hardware on the ground floor in the Artillery Park.

The lower level has two parts. The first is the ‘quiet area’ where there are displays of medical equipment; displays of military engineering equipment; the projectile room with displays ranging from stone cannon-balls to modern missiles; and the Chapel, dedicated to St. Barbara, the patron saint of the Artillery.

The Museum also holds the national collection of equipment, parts, motors and everything needed to operate the huge guns, installed as part of the 1926 Defence Plan in the four major naval/artillery bases around Spain. Some of which are still in place, for example in Portman.

In the main halls, we have one of the finest collections of large military hardware in Europe. It ranges from the muzzle-loading cannon of the 17th century, through the whole range of cannon of every description built through four centuries to the Roland missile launchers of recent times.

There are several surprising things to note. One is the vast amount of British equipment which was sold to the Spanish governments from broadly 1850 to the 1930s including the massive contract that Vickers/Vickers Armstrong had to supply the guns and equipment for the whole of Spain in the 1926 Defence Plan.

Less surprising is the amount of German equipment sold to the Nationalist side from 1935 until 1945, much of which the Spanish army used until the 1960s and some fine examples of which are held at the Museum.

Two particular items on display are worth describing. The (German) Mark III Stug self-propelled gun, mounted on a Panther III tank chassis, was restored and repaired by the volunteers. Bought from Germany in 1943, it was operational until 1954. Not only did the volunteers restore the exhibit, they also rebuilt the engine and it can still be driven around the complex.

There is only one tank in the collection, a Russian T-26 tank, one of 300 supplied to the Republican side. This model was built under licence from the UK company Vickers, as it is actually a re-designated Vickers 6-ton tank. It has taken several years to restore the tank to its present condition and work continues on the engine, though that too now works.

It is really impossible to adequately describe the Museum. The main courtyard is a delight, the artillery park could be visited ten times and you would still be finding new things and new pieces of information.

The rooms in the upper galleries containing the history of the City are, for me, quite special, as they show the development of Cartagena’s history over time and one of them – that dealing with the Guerra de Independencia, what we know as The Peninsular War – has led me back to doing the detailed research that I used to do professionally before I retired.

For anybody that lives close to Cartagena, the volunteers are always looking for new members to help in the Museum. For further details you can contact me at: tonyfullerresearch@gmail.com

All photographs are copyright of the Gobierno de Espana/Ministerio de Defensa and are used with the permission of the Director of the Museum, Commandante (Major) Juan Antonio Martinez Sanchez.